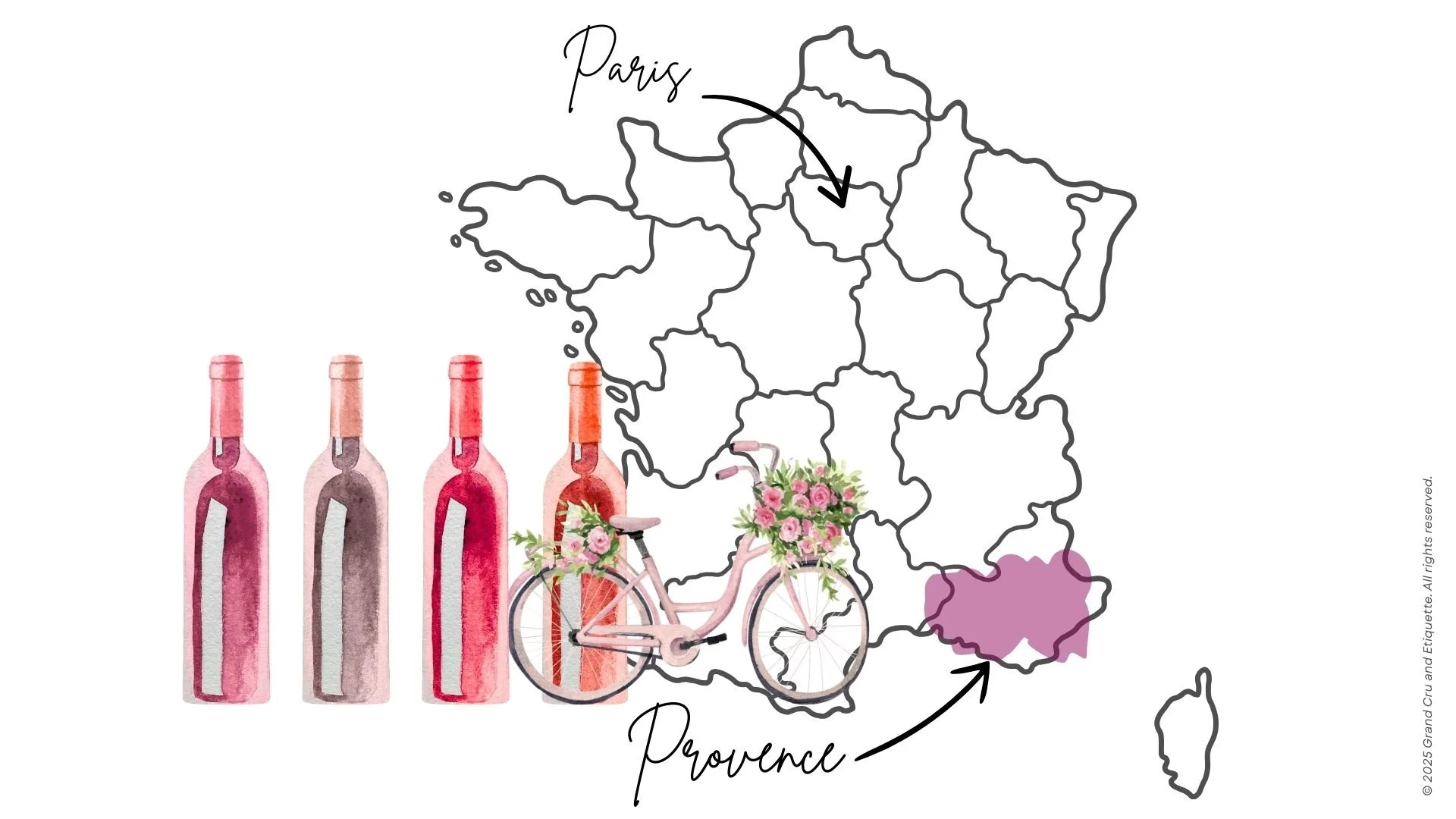

Provence Rosé: History of a Summer Icon

Provence rosé is now recognized worldwide as the ultimate summer wine. Its story blends tradition, innovation, and marketing, allowing it to become a symbol of freshness, conviviality, and light Mediterranean gastronomy.

“Farmhouse in Provence” by Vincent Van Gogh, 1888. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Birth and Evolution of Provence Rosé: Tradition Meets Innovation

Marcel Ott: The Man Who Revolutionized Winemaking in Provence

At the end of the 19th century, Marcel Ott, a young agronomist from Alsace, settled in Provence with his wife. In 1912, he acquired Château de Selle, now one of the 18 classified crus of Provence, and revolutionized local wine production.

Passionate about white wine, he chose to vinify rosé like a white wine, introducing the first macerated rosés. Ott also implemented a new, instantly recognizable bottle design, establishing the visual identity of Provence rosé. This innovative style quickly captivated consumers and helped establish the reputation of Provence rosé.

Rosé: A Symbol of Summer and Light Gastronomy

Tourism Boom and the Fresh Image of Rosé

During the 1930s, the rise of seaside tourism fueled by paid holidays made rosé the refreshing drink of choice for summer. It became closely associated with vacations, relaxation, and social gatherings.

A Popularity That Also Limits Recognition

Despite its fame, this summer-only image created challenges. Consumption remains highly seasonal, concentrated in the warmer months, making producers dependent on summer sales.

Rosé is often perceived as merely an aperitif wine, which limits its gastronomic prestige compared to the reds and whites of Provence.

Furthermore, consumers frequently choose rosé based on color alone, disadvantaging gastronomic rosés that are typically bottled in opaque glass.

How Provence Rosé is Made?

Winemaking Methods

Provence rosé is made from red grape varieties, but its vinification process limits pigment extraction to produce a pale color and fresh aromatic profile:

Direct pressing: grapes are pressed immediately after harvest, resulting in a light, aromatic wine typical of Provence.

Short maceration: the juice remains in contact with the skins for a few hours, producing rosés with more color and structure.

Contrary to popular belief, AOP rosé is never a mix of red and white wine, except in specific cases like rosé Champagne.

Sensory and Technical Analysis

Pale rosés offer floral and citrus aromas, refreshing acidity, and a light mouthfeel ideal for aperitifs and light dishes. More structured rosés, often incorporating Mourvèdre or Tibouren, feature ripe red fruit, subtle spices, and minerality. Flavor intensity and complexity vary depending on terroir, dominant grape variety, and vinification method (Loubet et al., 2014; OIV, 2018).

The Color of Rosé: A Recent Evolution

Historically Darker Shades

Originally, Provence rosés were darker and more structured, similar to Tavel rosés, which are the first and only AOP wines in France made exclusively as rosé since 1936. Tavel rosés sometimes exhibit orange hues and a more pronounced body, designed to accompany gastronomic dishes. These wines highlight how winemaking methods and maceration influence both color and flavor complexity (INAO, 2018).

The Rise of Contemporary Pale Rosé

According to the story, in 1981 a female winemaker crafted an extremely pale, petal-pink rosé. Although it was initially rejected by the INAO, Alain Ducasse later featured it in his Monaco restaurant. The pale shade quickly became the esthetic standard for Provence rosé, symbolizing freshness, quality, and modernity, a powerful marketing tool for the region.

Provence Rosé AOPs and Grape Varieties

The main AOPs producing rosé in Provence are Côtes de Provence, Coteaux d’Aix-en-Provence, and Coteaux Varois en Provence. Key grape varieties include Grenache, Cinsault, Syrah, Mourvèdre, and Tibouren. These blends create aromatic profiles ranging from red fruit and citrus to white flowers, forming the hallmark flavor of Provence rosé.

Key Figures

Provence rosé accounts for over 75% of France’s AOP rosé production and is the world’s leading producer of quality rosé. More than half of this production is exported, especially to the United States. In France, rosé now represents roughly one in three bottles of wine consumed, highlighting its cultural and economic significance.

Food Pairings: Rosé Beyond the Aperitif

Pale, light rosés pair with tapas, salads, sushi, and raw fish, while more structured rosés, such as those from Bandol or Tibouren, complement rich dishes like grilled lamb, spicy cuisine, or tagines. Fruity rosés are perfect with Mediterranean vegetables and cuisine. Provence rosé can be enjoyed year-round, not just in summer.

Myth vs Reality: Is Rosé a “Real Wine”?

In France, rosé is not a mix of red and white wine in AOP regions (except in Champagne).

Some rosés are complex, structured, and truly gastronomic.

Rosé can age. Certain terroir-driven rosés, such as AOP Bandol or classified crus, gain complexity after 2–3 years. Most, however, are meant to be enjoyed young.

A pale color does not indicate quality, only vinification style and maceration time. This contrasts with AOP Tavel in the Rhône Valley, which produces darker, more powerful rosés, whereas Provence rosés are pale, aromatic, and light.

Provence rosé is a sophisticated, versatile wine deserving full recognition for its diversity and quality.

From Summer Wine to Global Icon

Provence rosé has evolved from a beachside aperitif to a true ambassador of Mediterranean style. Its story exemplifies the successful combination of traditional expertise and modern innovation. Today, it stands as a gastronomic wine, a global marketing icon, and a cultural symbol recognized worldwide. Provence rosé is more than a summer drink, it is a complex, versatile, and prestigious wine capable of competing with France’s finest reds and whites.