French Winemaking Techniques: Step-by-step guide from vineyard to bottle

“Un millésime prometteur” Jan Moerman, 1886, (Pivate collection). Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Craft of French Winemaking: A Legacy of Excellence

France, a land where every glass of wine reveals a story. Behind every glass lies meticulous craftsmanship, shaped by the soil, the climate, and the passion of winemakers who patiently sculpt the unique flavors of each region.

Picture yourself journeying through sun-drenched vineyards, where grapes ripen slowly to give birth to an endless palette: deep reds, crisp whites, delicate rosés, festive sparkling wines, and rare treasures like Jura’s mysterious Vin Jaune or luscious fortified sweet wines, crafted with ancient techniques.

This article invites you to discover the essential stages of French winemaking, highlighting the regional nuances that give these wines their worldwide acclaim.

Red Wine Production

The Key Steps:

It all begins at harvest, often by hand, sometimes by machine, usually between September and October, the moment when grapes reach their peak ripeness.

Next comes the gentle crushing, where berries are separated from stems and lightly pressed.

Then the magical phase of maceration begins: skins immerse in the juice to release rich color and tannins, a natural dance between must and skin.

Pressing follows, separating precious juice from solids, before malolactic fermentation softens the sharp acidity into something rounder and more velvety.

Finally, the wine is aged, either in stainless steel tanks or oak barrels, gaining complexity and character before bottling, ready to reveal its soul.

Regional Signatures:

Bordeaux: famous for blends of Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon, aged long in oak barrels to achieve power and elegance.

Burgundy: home to Pinot Noir expressing the nuances of its terroir with unmatched finesse.

Rhône Valley: where northern Syrah and southern Grenache-based blends create a tapestry of bold and warm styles.

White Wine Production

The Key Steps:

Harvesting takes place earlier here, preserving the vital acidity that defines fine whites.

Immediate pressing prevents prolonged skin contact, maintaining purity and delicacy in the juice.

Next, the must is clarified during débourbage before fermentation, typically in stainless steel tanks, though sometimes oak barrels are used to add complexity.

Aging on fine lees imparts texture and subtle depth, before filtration and bottling.

Regional Signatures:

Alsace: the land of noble varieties like Riesling and Gewürztraminer, where slow fermentation preserves aromatic richness.

Loire Valley: home to vibrant Sauvignon Blancs and Muscadet aged on lees for added character.

Burgundy: Chardonnay shines here, often fermented and aged in oak barrels.

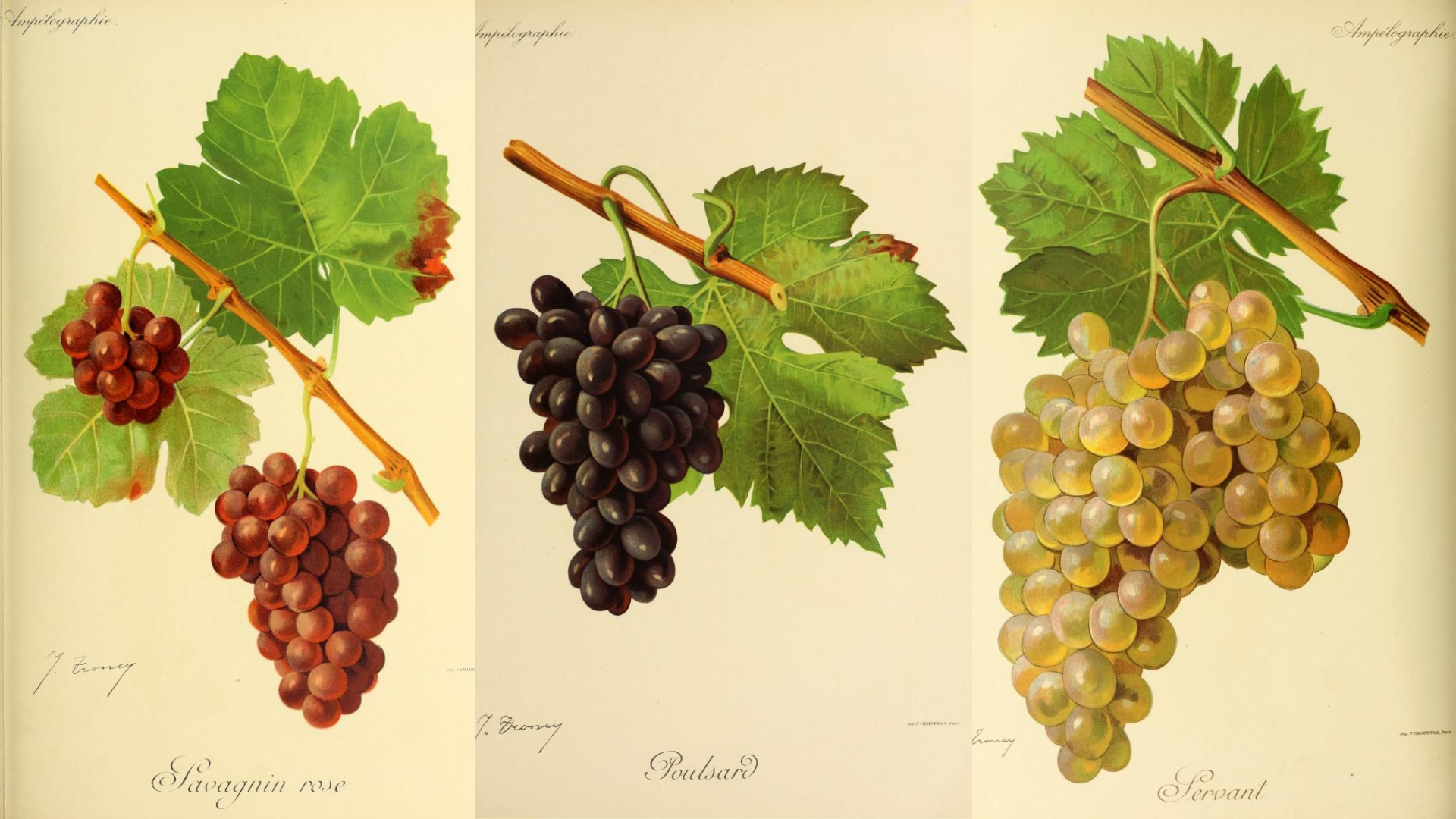

Jura and its Vin Jaune, made from Savagnin grapes aged 6 years and 3 months under a yeast veil, creating a powerful wine with distinct nutty and spicy aromas.

Rosé Wine Production

Three main techniques tell the story of rosé wines:

Direct pressing: It involves directly pressing red grapes (often with thin skins), which produces a very pale juice, typical of light and delicate rosés.

The saignée method: This technique involves “bleeding” off a portion of juice from red wine must after a few hours of maceration. The juice is then vinified as a rosé, resulting in a deeper color and often more pronounced fruity aromas.

Cool fermentation and short maturation: This helps preserve fresh, fruity, and floral aromas while avoiding oxidation or the development of heavy notes.

⚠️ Blending (mixing red and white wine) a 4th method to avoid confusing with the others: Prohibited under AOP regulations in France (except for rosé Champagne). Used in some table wines or rosés produced abroad.

Regional Signatures:

Provence: the global benchmark, producing pale, elegant rosés through direct pressing.

Languedoc: fruitier rosés often crafted by saignée.

Loire Valley: Cabernet d’Anjou, semi-sweet and aromatic rosés.

Sparkling Wine Production

The traditional method, also known as the Champagne method, is an art unto itself:

After a primary fermentation produces a still base wine, different crus or vintages are blended.

Then comes tirage, where yeast and sugar are added to the bottle, triggering a second fermentation that creates the signature bubbles.

The wine rests on its lees for at least 15 months (often much longer) before careful riddling, disgorgement, dosage, and labeling.

Regional Gems:

Champagne: the exclusive cradle of this method, featuring Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, and Pinot Meunier.

Loire Valley: home of Crémant de Loire made from Chenin Blanc and Cabernet Franc.

Alsace: the land of Crémant d’Alsace, crafted from Pinot Blanc and Riesling.

Sweet Fortified Wines (Vins Doux Naturels - VDN)

These sweet wines tell a story of time standing still, when nature’s sugar is captured and preserved.

Late harvesting concentrates sugars, fermentation begins, then mutage halts it by adding neutral grape spirit, preserving natural sweetness.

Aging takes place in tanks, barrels, or glass demijohns depending on the style.

Regional Treasures:

Roussillon with Banyuls and Maury, red VDNs rich and complex, aged oxidatively or reductively.

Muscat de Beaumes-de-Venise: white VDN bursting with exotic fruit and floral aromas.

Rivesaltes: available in red, amber, or tawny styles, shaped by grape and aging techniques.

French Winemaking: The Refined Art of Balancing Tradition and Innovation

Each style of wine, each bottle, is the product of a unique alchemy shaped by climate, grape varieties, and the centuries-old artistry of winemakers.

From the rolling hills of Burgundy to the terraced vineyards of the Rhône, from the elegance of Alsace’s crémants to the intensity of Jura’s Vin Jaune, the richness of French viticulture lies in this relentless pursuit of excellence.

To understand these methods is to dive deep into the very soul of French wine, a sensory and cultural journey like no other.

Discover more

FAQ:

Q01. What’s the difference between Champagne and Crémant?

Champagne is a sparkling wine produced exclusively in the Champagne region of France, following strict production rules (specific grapes, aging time, traditional method, etc.).

Crémant is also a sparkling wine, made outside Champagne (in regions like Alsace, Burgundy, Loire, etc.), but often using the same traditional method.

So, Champagne is technically a type of crémant, but not all crémants are Champagne. It’s mainly about region and designation.

Q02. What makes a wine dry, semi-dry, sweet, or dessert-like?

It all comes down to the residual sugar, the sugar that remains after fermentation:

Dry wine / Vin sec: Very little sugar (less than 4 g/L)

Off-dry or semi-dry / Vin demi-sec: A touch of sweetness (4–12 g/L)

Sweet wine / Vin doux: Noticeably sweet (12–45 g/L)

Dessert wine / Vin liquoreux: Very sweet, rich in sugar (often 45+ g/L), usually made from very ripe or botrytized grapes (affected by noble rot, or pourriture noble)

Q03. What is “dosage” in wine?

Dosage is a term used in sparkling wines like Champagne. After removing the yeast sediment (disgorgement), a mixture of wine and sugar is added to adjust the taste. Examples:

Brut Nature / Zero Dosage: No sugar added

Brut: Low sugar

Demi-sec / Doux: Noticeably sweet